South Korea / USA, Literature, 2019

Don Mee

Choi

I am a foreigner who writes in English / Because English is a foreigner like me – writes Don Mee Choi in her book Hardly War (2016). Born in South Korea in 1962, during the U.S.-backed military dictatorship, Choi escaped with her family to Hong Kong in 1972. A decade later they moved again, to West Germany, and a few years later to Australia – though by then, Choi was at university in the U.S. studying art before going on to do a PhD in contemporary Korean literature and translation.

She is now one of the foremost translators of modern Korean women poets into English. For her, translation is not simply a literary practice but an existential one: “It is what gives me home and, yet, it is what makes me a perpetual immigrant.”

Don Mee Choi’s own writing – three published collections, including The Morning News Is Exciting and Petite Manifesto – is preoccupied with the condition of displacement between geographies and languages, memories and histories. In the poetic domain she shuns any placatory conciliation of difference or distance. “I refuse to translate” – she asserts five times in Hardly War, ending the emphatic stanza with “5=Over”. Such word-sums recur in her poems: Race=Nation Purely=Utterly me=gook Ugly=Nation President=For Life! Ugly=Translators S=SEX=FILE=EASY Hardly=Humans. Broken equations with no solution, only an eternal working out that may or may not add up.

For the past thirty years Choi has lived in the US: “…And what do my translations say to the readers of this nation? Korea is not a foreign nation? It is a mini spectacle of the US?” Her poems carry similar echoes: Korea described as “Neocolony’s Colony”. She grapples constantly with the im-possibility of using English – a colonial language – even as she superbly subverts it, seeking an end to “end to grammar of obedience and colonialism”: quoting Deleuze and Guattari´s A Thousand Plateaus, there is no mother-tongue, only a power takeover by a dominant language. Her poems strive to give power the slip with other sounds, other stories: Me, countless, out to tear. Sane no, lend me. / Say I can’t rain, end me.

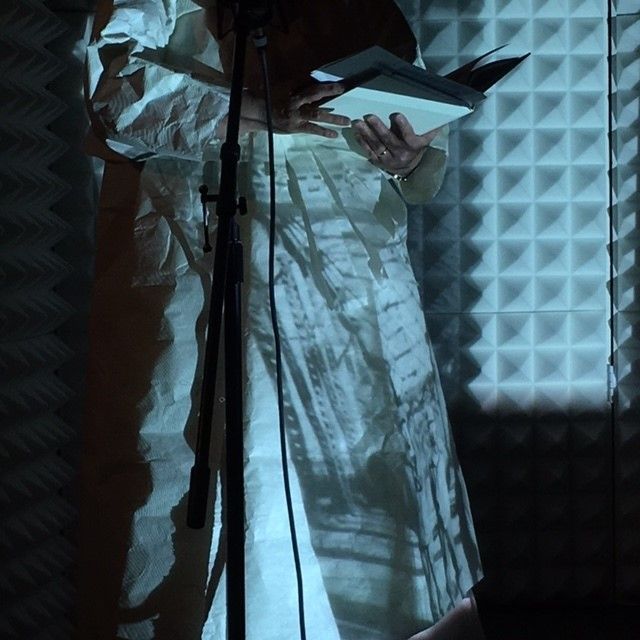

Don Mee Choi’s writing, slides between forms: memoir, libretto, list, diary, visual poetry, essay. Hardly War is a hybrid text about all the violent conflicts her father saw as a war-photographer and includes pictures he took. Woe is you, woe is war, hardly war, woe is me, woe are you? “I am trying to fold race into geopolitics and geopolitics into poetry,” she writes. “It involves disobeying history, severing its ties to power. It strings together the faintly remembered, the faintly imagined, the faintly discarded.” Reds dead without a mark on them (hence hardly) Thus Choi arrives by degrees – it was partly history… I was narrowly narrator… – at a whole, which nevertheless remains wilfully partial.

“My primary technique for translation and my own poetry is failure,” Don Mee Choi has reflected. “We have no choice but to failfail.”

Text: Priya Basil