Nigeria, Literature, 2024, in Berlin

Logan

February

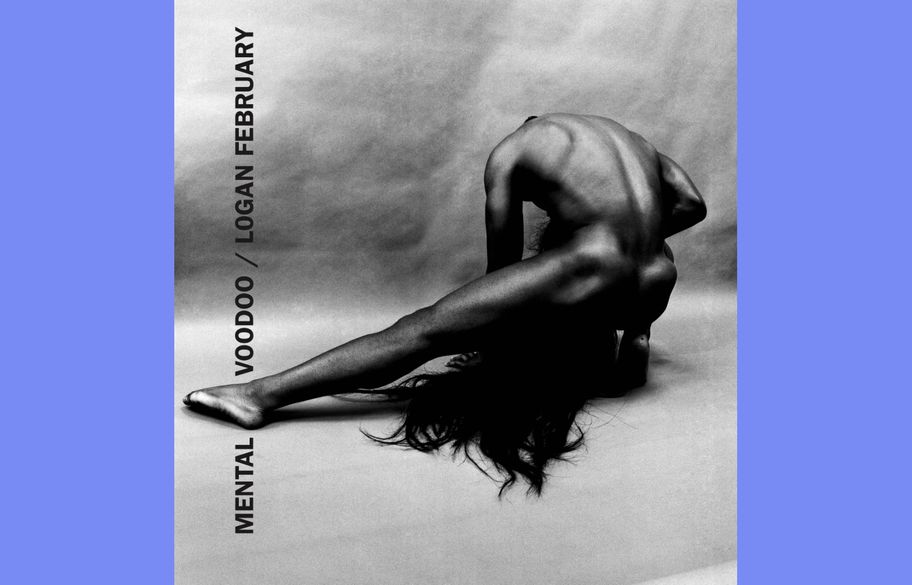

MENTAL SPACES

Logan February’s poetic rituals

“Think of it as your very own voodoo, magic / coursing through your body.” In an interview, Logan February once described their work as a form of mental voodoo. And in fact, a kind of sympathetic magic sets in while reading their poems, which instinctively invokes the oldest Yoruba traditions while simultaneously remaining a physical part of the queer present: “Skin translates to flesh translates to body.” The line speaks of one’s own skin, which cannot be embodied, except in translation. How do these texts, linguistically speaking, accomplish their miraculous glide from physical to metaphysically charged objects, from Yoruba traditions to the present and back? And where do the symbolic boundaries lie in these flows that refuse all binaries?

Logan February, born 1999 in Anambra, Nigeria, is a non-binary poet, essayist, singer, songwriter, and LGBTQ activist. In addition to publications in literary journals, they have so far released three chapbooks—How to Cook a Ghost (2017), Painted Blue with Saltwater (2018), Garlands (2019)—and the poetry collection In the Nude (2019) as well as translations into Spanish, Italian, and Dutch. In 2020, Logan February was awarded the Future Awards Africa Prize for Literature.

“So I sing to your rotations.” As Stephane Mallarmé’s eponymous poem from 1874 shows, the demon of analogy—Le démon de l’analogie—is a phenomenon of parallel languages. And once that earworm has settled in, the demon starts sounding like a song on repeat. The eternally old song creates connections with the absent and the dead, “La Pénultième est morte.” But the more the sentences take on lives of their own, the more spatial they become— the more they become like objects capable of storing what we project onto them. Many dead bodies are inscribed in Logan February’s poems, the many queer dead of societies that exclude other bodies, other ways of life and—as in Uganda—persecute them to this day with the death penalty.

“Tell me / what you know of me / Am I truly a river.” One secret of Logan February’s verse seems to me to lie in its processual character, in its ability to keep things flowing without drifting into arbitrariness. The figures in these poems don masks that aren’t disguises, but allow their wearers to become what they present. Thus, the mannequins in a series of self-portrait poems can be both lovers and beloveds. The space between signifier and signified implodes. For the mannequins also take on the forms of those familial inheritances that can inscribe themselves in the neuroses of any love relationship. Thus, the act of queering is not just a thematic assertion, nor the queering of identities, but a linguistic process, a play with speaking positions: “your clicking and clacking into the shape of it.”

It’s a great pleasure to follow the way Logan February’s texts thwart the common binary thinking patterns. African and European discourses, the ancient knowledge of the Òrìshà corpus and insights from psychoanalysis, decolonial and queer studies are not at odds; they permeate each other. And it doesn’t happen by way of some retroactive mental construct, but through the experience that things are in fact always already contaminated. There is an “inherent queerness of tradition,” says Logan February. And they see it as a birthright to claim the right to a queer life in Nigeria. No purity, no innocence is defended or claimed in these texts, not that of nations nor of bodies. Oh, if only we would realize that we’re always already “fucked” … But until that becomes common knowledge, reading these poems can prove extremely helpful: “From the prism of the swirling, / I learn that you can still look pretty / in the middle of ruin.”

Text: Christian Filips

Translation: G&C Art Translators