South Africa, Literature, 2014

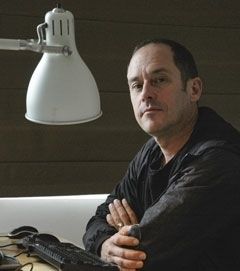

Charl-Pierre

Naudé

Charl-Pierre Naudé, born 1958 in Kokstad, is regarded as one of contemporary South Africa’s most interesting and promising poets. Both his parents have Huguenot ancestors. He himself grew up in Durban, and later in East London (Ostkap), on South Africa’s southeast coast. In his youth, he experienced the world of Ostkap – populated with the myths and legends of the Xhosa people – as a magical world.

Yet society at that time, strictly divided according to race, was an inescapable truth, and already at an early age he found this system inhuman. This moment of awareness serves as the turning point in his defining himself a “white” South African, which, reflected in his poetry, he questions even today – if secretly and between the lines. In this sense, Naudé represents an entire generation of younger poets, who found their voice less so in the shadow of the Soweto Uprising than in the twilight of the post-apartheid period, spread over the dichotomy between the collapse of the old and fragile constructing of a “new” South Africa, in which the euphoria of an awakening was soon forced to yield to disillusionment. Naudé first appeared on the South African poetry scene in 1995, with his volume of poetry, “Die nomadiese oomblik” (The Nomadic Moment), awarded the 1997 Ingrid Jonker Prize, created to annually honor exceptional poetry debuts written in English or Afrikaans. Naudé, by the way, is fluent in both languages. And, like everyone of his generation, he grew up contemplating the question: Who writes what for whom in which language? His second likewise prize-winning volume of poetry, “In die geheim van die dag” (In the Secret of the Day, 2005), appeared in 2007 as an English-language edition entitled “Against the Light” – for which he insisted on the English version not being merely a translation, but rather a transcription of the original volume: one poet, two languages, and two different perceptions of the world. On the other hand, Afrikaans – formerly the dominating language of the “ruling class” and now “marginalized” as one of South Africa’s eleven official languages, forced to accept the need to re-establish itself in literature – is a language he deems thoroughly mixed and characterized, as such, by intra-cultural translations. Naudé’s debut already pointed towards linguistic elements that are typical for his poetry today. These include the deliberate but also deliberately ironic, fractured recourse to classical forms (like the sonnet) as well as poetologies. Prometheus, Aphrodite, Lesbia, and the Cyclopes haunt his poetry to the same extent as the two ancient poets Catullus and Horace, who Naudé involves in a fictional competition to find out which of the two is the better poet. When asked, during an interview, to comment on the role of both poets in his own work, he explained: “For me, they are prototypes of two poetic attitudes, both of which influenced the subsequent western poetry. But more importantly, for me, is that Horace advocated the state and order; Catullus opposed the state, he also opposed strict order. And this is precisely the problem that South African writers face today. Once again they find themselves in a situation where the choice is not as simple as it appears to be.” (in: Bernard Odendaal in Conversation with Charl-Pierre Naudé. Tydskrif vir Letterkunde 45.2, 2008, pp. 184 – 193). In any case, Naudé decided in favor of Catullus, whose poems, despite turbulent political upheavals, were never per se political. Instead, they invariably put stock in the impetus of what one experiences. To that effect, the political is also present in Naudé’s poetry – but it always splinters into prisms of the personal: In “How I Got My Name”, for example, using the humor meanwhile typical for his writing, he gives thought to his Huguenot first name, abbreviated in pidgin language, with its two halves connected by a hyphen – for him a “concise story of colonization”. He bursts the (often transfigured) history of South Africa by going against its grain and capturing in garish vignettes the socio-political challenges of the post-apartheid’s present-day, whether AIDS, xenophobia, or the continuing unequal possession of property. Still, what invariably dominates his poetry is the narrative moment. This is because Naudé – influenced by the work of his South African colleague, Breyten Breytenbach – has a strong preference for allowing foreign, visual particles to collide, which, in turn, lends his poems their dreamlike, surrealistic character. For this reason, they often read like wild acts of stream of consciousness, perhaps filled with sensual details of the tangible world – in which “the foreign and the familiar constantly crash into one another without there being a formula for how to react”, writes Indra Wussow in the epilogue of the poetry anthology “The Arrival of Another Day”. And again, like so many of his generation, Naudé, too, searches for the new and genuine “South African” perspective, the one able to encompass more than just the geographical extensions of his native country. “How to write about Africa? Can it be done?” asks Breyten Breytenbach in the introduction of an instructional volume programmatically entitled “Imagine Africa”, published in 2012, and to which Naudé contributed as an author. Ideally, as Breytenbach suggests, “imagining Africa” means: writing about it as an historical subject beyond the usual tropics of exotic romanticizing or defeatist condemnations, and to embark on a journey into a future as filled with the dreams of a promising tomorrow and finding a voice as with the silenced spirits of a painful past. South Africa’s Catullus, Charl-Pierre Naudé, seems to manage this without the slightest effort.

Text: Claudia Kramatschek

Translation: Karl Edward Johnson

The Arrival of Another Day. Contemporary Poetry from South Africa. Selected by Indra Wussow. German translation by Sylvia Geist. Afrika Wunderhorn Series. Verlag Das Wunderhorn, Heidelberg, 2013, pp. 22-37