Lebanon, Visual Arts, 2017

Lawrence

Abu Hamdan

Lawrence Abu Hamdan works at the interfaces of sound and politics, focusing in particular on the act of hearing and listening (“politics of listening”). His projects take the form of audiovisual installations, performances, graphics, photographs, Islamic sermons, audio-tape compositions, potato chip packaging, essays and lectures. His audio-aesthetic research focuses on the forensic investigation of sound material—often in collaboration with the Forensic Architecture research agency at Goldsmiths College London. The agency’s primary purpose is raising awareness of specific political issues—for instance, by creating a virtual 3D-model of Assad’s Saydnaya torture prison, previously a blind spot on the Amnesty International map, based on the statements of “ear-witnesses.” Since prisoners were deprived of their visual senses for extended periods of time, the prison’s architecture, in functioning as an echo chamber, itself became an architectural instrument of torture. The model raises awareness and serves as a memory of this horrific place.

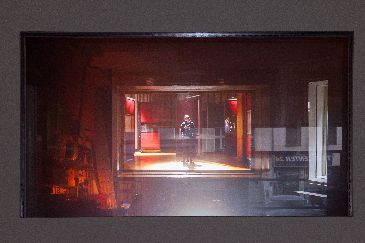

The material for the exhibition Earshot 2016 at Portikus in Frankfurt originated in an investigation conducted by Forensic Architecture and Abu Hamdan on behalf of the human rights organization Defense for Children International. The point of the investigation was to resolve the violent death of two unarmed Palestinian teenagers in 2014 by Israeli soldiers in the occupied areas of the West Bank. In a technique designed to visualize sound frequencies, an audio-ballistic analysis of recorded gunshots clearly demonstrated that the soldiers had not used rubber bullets, as they claimed, but live ammunition, and that they had also attempted to cover this up by “disguising” the projectiles with rubber casings. The main video installation of the exhibition, Rubber Coated Steel, functioned as a symbolic tribunal of the projectiles that killed Nadeem Nawara and Mohamad Abu by amplifying the silence of the victims’ voices.

The Hummingbird Clock, produced in 2016 for the Liverpool Biennale, consisted of an intervention in public space permanently installed across from the courthouse in Liverpool as well as a web component. The sculpture—a “tree” of three binoculars in the form of surveillance cameras pointed at the courthouse’s clock—is intended as a means of counter-surveillance. Variations produced every second in the inaudible but constant humming of the electrical grid are seismographically recorded and archived and can be accessed upon request. With this database it is possible to chronologically index digital recordings with fingerprint-like precision—a technique the British government has already been using for ten years as a method of survelliance.

The installation A Convention of Tiny Movements (2015) is based on the results of a research group at MIT, according to which the surfaces of particular everyday objects or their packaging, act as recording devices when activated by sound vibrations. It is interesting to note that these objects incorporate the human voice within their own sound. The installation, consisting of, among other things, a recorded message presented in a “whisper cube” and a set of 5,000 packets manufactured specifically for potato chips, presents a disturbing scenario of monitoring possibilities in the not-too-distant future.

Text: Eva Scharrer